From the example of the sunset picture in installment #1 of this photography basics series, you have learned the importance of taking full control over the exposure on your camera. Now, it's time to dig into your camera and learn the three most basic tools available to you in controlling the exposure.

Those tools are shutter speed, aperture, and ISO. After I explain what each one does, I'll explain why we need three separate tools to control the brightness or darkness of the photo.

Aperture

A small aperture in a camera lens.

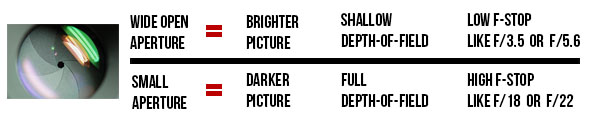

So suppose you take a picture that is too bright. How do you fix it? Simply choose a smaller aperture. Simple! Aperture sizes are measured by f-stops. A high f-stop like f-22 means that the aperture hole is quite small, and a low f-stop like f/3.5 means that the aperture is wide open.

Let's test your knowledge to make sure you have it down. If you take a picture and it's too dark at f/5.6, would you choose a lower f-stop number or a higher one? Yep! You'd choose a lower f-stop number, which opens up the aperture to let in more light. The size of the aperture controls more than the brightness or darkness of the picture, though.

The aperture also controls the depth-of-field. Depth-of-field is how much of the picture is sharp, and how much is blurry. If you want to take a picture of a person and have the background be blurry, you'd use shallow depth of field. If you want to take a picture of a sweeping mountain vista, you'd want to use a small aperture size (high f-stop number) so that the entire scene is in sharp focus. If you, like me, are more of a visual learner, then I think this graphic will help solidify the information about aperture. Take a minute and make sure you understand this info before moving on.

.

Shutter Speed

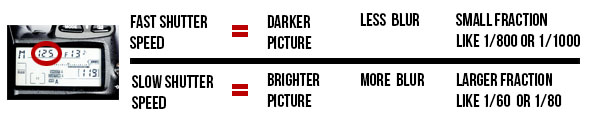

The shutter is a small “curtain” in the camera that quickly rolls over the image sensor (the digital version of film) and allows light to shine onto the imaging sensor for a fraction of a second. The longer the shutter allows light to shine onto the image sensor, the brighter the picture since more light is gathered. A darker picture is produced when the shutter moves very quickly and only allows light to touch the imaging sensor for a tiny fraction of a second. The duration that the shutter allows light onto the image sensor is called the shutter speed, and is measured in fractions of a second. So a shutter speed of 1/2 of a second will allow more light to touch the image sensor and will produce a brighter picture than a shutter speed of 1/200 of a second. So if you're taking a picture and it is too dark, you could use a slower shutter speed to allow the camera to gather more light.

That's me! Typing away on this article from my studio in Meridian, Idaho.

Imagine me sitting here at my computer desk waving to you (you don't have to imagine very hard if you just look at the picture on the right).If you take a picture of me with a shutter speed of 1/30th of a second, then my hand will have moved in the time that the camera is recording the picture. To get rid of the blur, you need to increase the shutter speed to around 1/320th of a second. At this speed, my hand is still moving, but the camera takes the picture so fast that my hand travels only such a small distance that it is not noticeable in the picture.

The next question that most people ask is, how slow of a shutter speed can you use and still get a sharp picture? Click here for a blog post that answers that exact question.

ISO

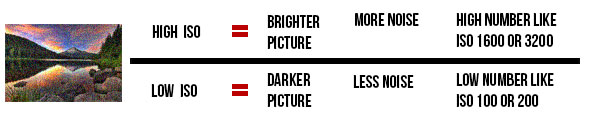

The funny thing about ISO is that it is an acronym, but nobody really knows what it stands for. It is always just called ISO even though it really stands for International Organization for Standardization. Every once in a while, you'll hear an older photographer pronounce it “I-so”, but almost everyone pronounces it “I.S.O.” The ISO controls the exposure by using software in the camera to make it extra sensitive to light.A high ISO such as ISO 1,600 will produce a brighter picture than a lower ISO such as ISO 100. The drawback to increasing the ISO is that it makes the picture noisier. Digital noise is apparent when a photo looks grainy. Have you ever taken a picture at night with your cell phone or your pocket camera, and noticed that it looks really grainy? That is because the camera tried to compensate for the dark scene by choosing a high ISO, which causes more grain.

What constitutes a “high” ISO is constantly changing. Camera companies are constantly improving the ability of cameras to use high ISOs without as much grain. A few years ago, only the highest-end pro DSLR cameras could achieve 2,000 ISO, and now even entry-level DSLR cameras can shoot at this level. Since each camera is different, you would do well to do a few tests with your camera to see how high of an ISO you can shoot at without making the image overly grainy.

Right now, you will commonly find new DSLRs that advertise expandable ISO ranges. To learn more about that, click here.

Putting It All Together

I know exactly what you're thinking: “Why do I need three tools to control the exposure!?!? Wouldn't one suffice?” The answer is no, and I'll explain why with an example. In January 2012, I took a trip to my favorite place on the planet to take pictures–Yellowstone National Park. My guide informed us that the bighorn sheep in the park were dying off very quickly due to whooping cough, so I worked hard that week to capture pictures of the last few sheep in that area of the park. Around 9AM on a cloudy day, I found a small group of bighorn sheep and started photographing them with a long 600mm lens. The early hour and clouded sky made the situation quite dark for shooting.The lens I was working with (which costs $11,000–don't they know I've gotta send my kids to college?)… Anyway, it had a maximum aperture size of f/4. So I set my aperture at f/4 to gather as much light as possible. This also impacted the depth-of field to blur out the rocks behind the bighorn sheep. Next, I set my shutter speed. I wanted to capture action in the photo, so I set my camera to 1/1000th of a second shutter speed. I knew that this fast of a shutter speed would prevent any motion blur from the sheep running on the mountain side. Then, I took a picture. WAAAY too dark! I couldn't compromise my shutter speed or aperture, so I knew I needed to use the third player in the exposure triangle–the ISO.

I played around with my ISO and found that if I increased it to ISO 640, it made the picture bright enough to take the picture without making it overly grainy. Yahtzee! This combination of shutter speed, aperture, and ISO worked out perfectly. Now can you see why you need to know how to shutter, aperture, AND ISO, and know how to set them independently on your camera?

Click the link below to continue reading this totally free photography basics series of articles, but if you're more of a visual person and want to see how to set the camera settings for various situations, you should really check out Photography Start.

If you're a visual learner and want to really learn your camera, then be sure to check out my beginner photography class, which I call Photography Start. It's a series of 22 short videos where I take you on location to shoot waterfalls, landscapes, people, kids, and macro photos. You can look over my shoulder and see exactly how I set up my camera to take professional photos. Best of all, the video series is priced REALLY reasonably at just $15. Check it out here.

In part 3 of the Photo Basics Series, I'm going to teach you how to set these on your camera.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.