Film Photography Benefits: Why I Still Shoot on Film (and You Should Too!)

Helps you Learn the Basics

The great thing about film cameras (especially the older ones) is

that they force you to learn what each part of the camera does before

taking a photo.

This is something that many amateur photographers overlook when they get

their first camera; they’ve seen what it can do and just want to start

taking photos. It often results in the camera being left in full auto

mode or a preset when, with just a few clicks of the dial, much better

photos could be taken.

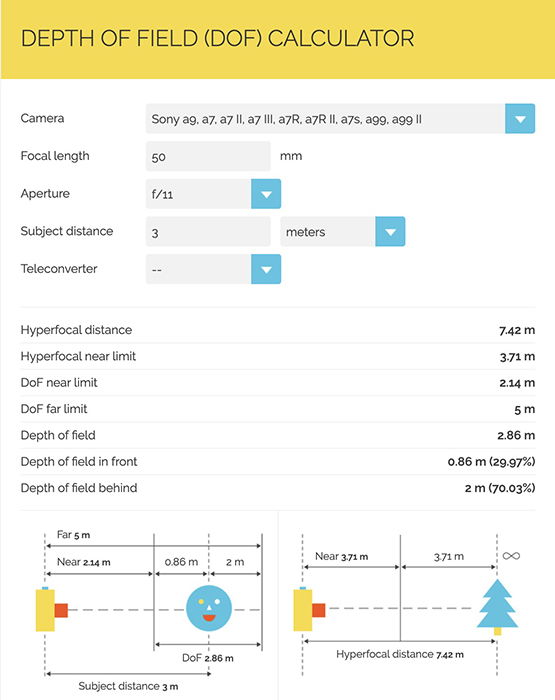

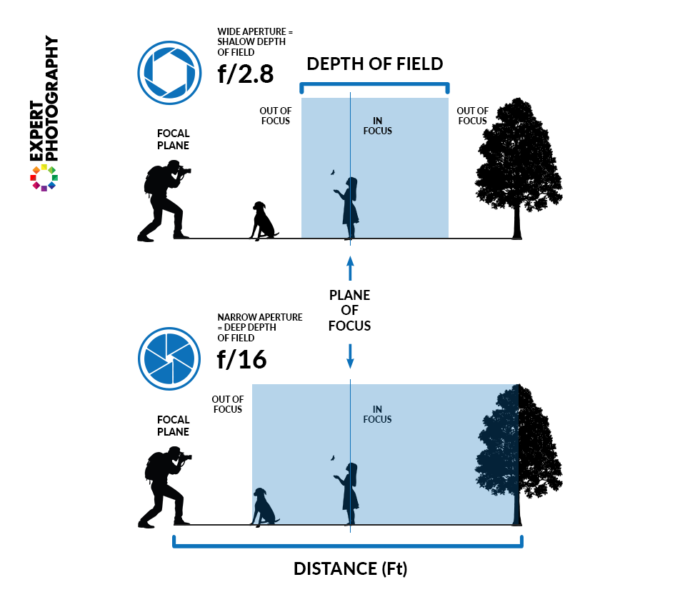

When you choose a roll of film to put in your camera, you’re effectively

setting the ISO speed as you can’t change the film until you’ve

finished, leaving just the shutter speed and aperture to play with.

When you take photography back to basics like this, you quickly start to

learn how exposure works and how to use it to your advantage. If you’re

a kinaesthetic learner like me, you’ll find film cameras a much more

effective way of learning about photography.

It Helps to Hone your Skill

We’re all guilty of getting a little bit snap happy with our

cameras, taking a load of useless photos of nothing in particular just

because we can.

This isn’t really an option with film (unless you’ve got more money than

sense) because you can’t just take a bunch of photos and transfer them

to your computer.

Film forces you to think before taking a photo – it can’t just be of anything.

This added pressure of wasting money on film and developing will make

you a much more careful photographer; you’ll start considering how else

you might take a photo before actually taking it.

Think twice, shoot once.

Mistakes can become pretty expensive if you’re not sure what you’re

doing with your film camera, which forces you to learn quickly what

you’re doing wrong.

There will be times when you go to take your camera out, adjust the

aperture and shutter speed, manually focus and end up missing the shot.

This is ok; it’s all part of the learning process. You’ll soon get

faster and better at using your camera; transferable skills to digital

photography.

Don’t worry about missing a shot; we all do that. The chances are, if you wait a little bit, you’ll get an even better photo.

Film Photography is Cheaper

The cost of second hand, top quality film cameras has dropped

dramatically since the advent of cheap DSLRs, making it a great time to

get into film photography.

Just because a lens doesn’t autofocus or fit onto a modern day camera,

it doesn’t mean it’s no good. One of the best lenses I have is a cheap

50mm f/1.7 that fits onto my Minolta with a bayonet mount.

Old prime lenses without autofocus have very few elements to worry

about, meaning that that the overall quality tends to be better.

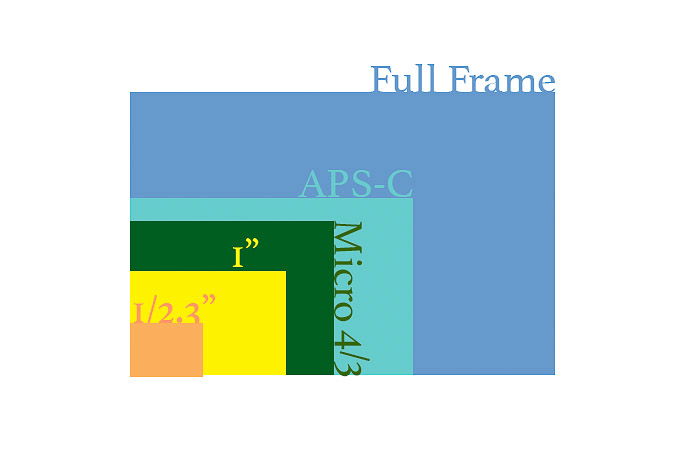

Another great advantage is that you can get a ‘full frame’ camera for

less, meaning that you get the most out of any full frame lenses you may

have.

I’m a Canon shooter and all their EF lenses from 1987 onwards fit on both their EOS digital and film cameras.

This means that I can spend money on a lens and still be able to use it on my film camera, in full frame.

I won’t go into too much detail about full frame cameras, I’ll just link to this post but what I will say is that modern digital full frame sensors are called ‘full frame’ because they’re the size of a 35mm piece of film.

If you don’t have a full frame camera, using film is a great way of seeing what you’re missing and from a different perspective.

Better Quality

The first thing I noticed when I got into film photography was the difference in quality – it was shocking.

A camera’s sensor is simply an expensive imitation of the roll of film that is no way near film technology, from decades before.

Not only that but a camera’s sensor is limited to a built in number of

pixels, whereas a roll of film is only restricted by the quality of the

scanner that captures it – usually much higher. Remember, you can still

get digital copies of your photos when you go and get them developed.

All of that aside, I just find photos shot on film to be sharper.

Better Color

The color of the photos produced are much better than on digital as a

roll of film isn’t limited by the same restrictions as a sensor.

Not only that but you don’t have to worry nearly as much about pesky white balance when shooting on film.

Have a look at the photo below. This is one of my favourite

photos because of how well it has captured the purple, red, blue and

brown without losing any detail.

This was shot on my Minolta SRT 101, a from the 1960’s.

Better Dynamic Range

Another thing I noticed when shooting on film was that I could shoot

in conditions that I wouldn’t normally be able to and still get good

result.

This came from the dynamic range of the film that I was shooting on; if

you have a look at the photo below, you’ll see trees that would

have appeared as silhouettes had I shot them on digital, with a lot

more detail.

Film is more Sensitive

In general, I find film to be much more sensitive and better at handling grain than any digital camera I’ve used.

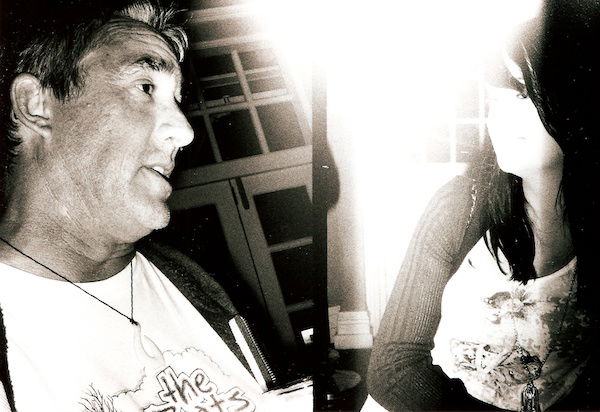

Have a look at the photo below and you’ll see that, even though there is

noise present, it’s a uniform color and appears much smoother than it

would shot on digital.

The speed I shot at was ASA 200, which provided excellent results for the conditions I was shooting in.

This photo is another great example of how the dynamic range is better

in film photography; there’s no way my camera’s sensor would have

handled that shot as well as the film did.

Physical Photos

You can shoot all day long on digital but it doesn’t mean much if you

end up just looking at them once before storing them to be lost on your

computer.

It’s great to have physical copies of photos that you can frame and hang

around the house to be seen – the way photos were always supposed to be

handled.

What to Watch out for

No matter how much I rant and rave about film photography, it’s still

a dated technology, so you will end up having to buy second hand.

Find a good second hand retailer nearby and you won’t have too many

problems; they know how to check the cameras before selling them and

will guarantee anything they do sell.

That being said, make sure you check the camera yourself; you can’t retake holiday photos that don’t come out.

I once bought a camera, took it on holiday with me and it wasn’t until I

got home and had the photos developed that I found that the shutter

wasn’t going up fast enough, ruining my exposures. I had it replaced

without hassle for a better camera, but the damage had already been

done.

If you buy a rangefinder as opposed to an SLR, you will always end up

leaving your lens cap on for a few photos here and there – I’ve done it

many times.

You become so used to being able to see your photos framed through a

viewfinder that you forget that the viewfinder is not connected to the

lens on a rangefinder camera.

Something a little bit rarer is “light leaks”. These are usually found on much older cameras for a variety of reasons.

In my photo below, I was using an old Olympus Pen (which used to shoot

two shots to every frame). The tripod mount fitting had fallen out of

the bottom of my camera which allowed loads of light in. This ruined the

centre of each exposure.

Interestingly, there’s a sub-genre of film photography that uses

analogue cameras and aims for a lo-fi aesthetic which actually favours

images with light leaks and other imperfections, which were common in

cheaper analogue cameras from decades ago.

The point behind embracing the imperfections is nostalgia, as light

leaks, lens artifacts, etc. were hallmarks of a bygone era of film

photography that many still remember from their childhoods. In fact,

this imperfect look influenced many of the filters so common today on

Instagram and other social media.

I still shoot film because it helps me be a complete photographer. When

you care about the image, you should be able to master it across media,

whether analogue or digital. There are certainly a lot of lessons to be

learnt when shooting on film, especially if you’ve started out learning

photography with digital cameras, but the results are always worth it.

I still shoot film. Years from now I know I’ll be saying the same, and I hope you will too.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------