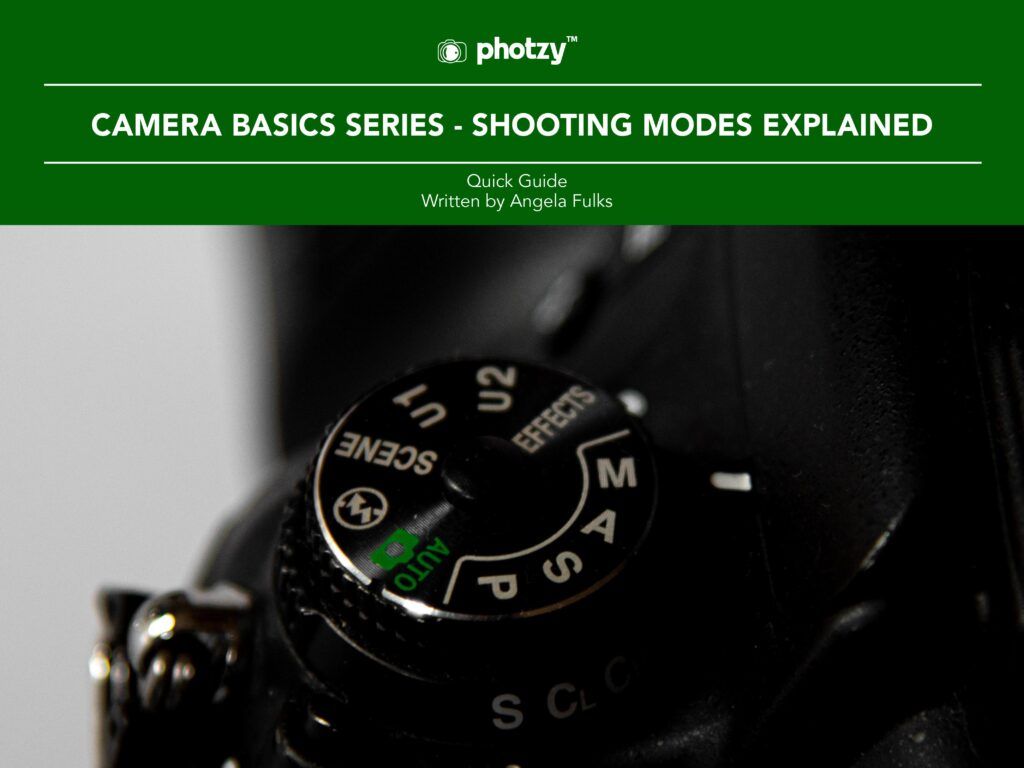

There probably isn’t a more confusing and misunderstood topic on the camera side of photography than the shooting modes.

Shooting modes may be incredibly confusing to people just starting in photography; after all, there are so many letters and icons on that mode dial! What do these letters and icons mean?

Good question! And the sooner you understand them; the earlier your photography will improve and become more predictable.

This is what will be covered in this guide:

There are those that believe that the manual mode is the only mode that a real photographer uses.

We don’t believe that. There are reasons that all of these different modes are available to photographers, even on the most professional level DSLR cameras.

Each mode has a purpose.

Are you ready to learn about them? Let’s go!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

By Josh Dunlop

When a frame is divided by a single, dominant line, more often than

not this is due to a Horizon. They’re fairly common in outdoor

photography, particularly landscapes.

If the photo is of nothing particularly interesting, this line can

become the dominant part of the photo for the way it separates the

frame.

Firstly, I think it’s important to realise where

you don’t want to place the line, and that’s directly in the middle of

the frame. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t ever it, this just has a

tendency to divide the photo in half, creating an uneven photo.

The contrast between the two halves makes it look more like two separate photos.

Exactly where you place the horizon is completely up to you but it helps

to remember that, if a feature of a photo does nothing to improve it,

it has no place in the photo to begin with.

Here’s a photo where the horizon has divided the frame in two. Notice that it doesn’t really favor either half.

If you take the horizon and place it slightly lower in the frame, you

regain a feeling of stability which balances out the photo better.

You also remove the feeling of division and the whole photo starts to

come together as a single image made up of multiple elements, rather

than just two photos stuck together.

Have a look at the photo below to see what I mean.

If you were to decide that the top half of the frame was much more

interesting than the bottom, you may want to adjust your composition so

that the horizon is a lot lower in the frame.

The photo below was taken from a tower in London on a rainy day with emphasis on the sky.

The cityscape adds an interesting texture to photo but holds much less

visual weight. It serves to make the man made city look small in

comparison to the powerful sky and weather.

This is one of the many interesting, extra feelings which can be evoked

when you consider the importance of different aspects of a photo and

adjust your composition accordingly.

The photo below was taken directly after the photo above and focuses largely on the ground, rather than the sky.

This photo contrasts greatly with the one above because it doesn’t evoke

the same feelings, instead focusing more on the colour and lines in the

city.

Your eyes are naturally drawn up the photo from the colour of the trees

and houses at the bottom of the frame to the sharp and jagged nature of

the buildings by the sky at the top.

An equally interesting photo but for different reasons, all because of

the decisions made over the placement of the horizon. Importantly

though, you’ll see that both images are stronger than the original image

which cut the photo in half.

If you want to include both the sky and the ground but don’t want to cut

the photo in half, I recommend changing the orientation to portrait.

Again, you’ll probably want to avoid placing the horizon in the middle of the frame but the decision is up to you.

I personally feel that the composition in the photo below is stronger

than any of the photos above as it includes the most interesting parts

of each photo.

The weather had changed slightly between photos, meaning that there was

less uninteresting sky in the photo. This certainly helped towards

finding the perfect balance between sky and ground.

It’s all about thinking it through and experimenting with what works for you.

Now that we’ve covered why you want to include a high or a low horizon, let’s have a look at some examples.

The high horizon in this photo was an obvious choice as the sky

was particularly plain and uninteresting on the evening that I took this

photo.

Realising this, I made a special effort to include the foreground a

little bit more to strengthen my photo. I found these strong, jagged

rocks which contrasted nicely with the sky while blending in with the

colour of the photo.

Below is an extreme example of a high horizon – I chose to include it

because it focuses the interest onto the subject and foreground below.

It makes it look as though the visual weight of the subject forces the

camera down, at the same time keeping the photo stable by remaining

straight across the top of the frame. There’s a lot going on in the

lower half of this photo and the inclusion of the sky would have

distracted from this.

Photos of clouds from below can be pretty boring

and rely heavily on being ‘pretty’ for attention. If you raise your

angle, the clouds rely more on their shape and form to attract viewers.

Because I had a higher vantage point and the shape of the clouds was

particularly interesting, I chose to include as much of them as

possible, which meant using a lower horizon.

I included just enough of the ground to make the colour interesting and

complimentary to the colour of the sky, while focusing most of the

viewers attention towards the subject: the clouds.

This is an example of a very low horizon. I chose to take the photo this

way not because I wanted to emphasis to be on the rather uninteresting

sky, but because I wanted to focus on the dominance of the building.

With the horizon that low, the feeling of balance is lost which draws

your attention towards the bold building standing on top of it. By

removing many other potential features from the frame, you focus the

attention onto one specific point – the building.

There probably isn’t a more confusing and misunderstood topic on the camera side of photography than the shooting modes.

Shooting modes may be incredibly confusing to people just starting in photography; after all, there are so many letters and icons on that mode dial! What do these letters and icons mean?

Good question! And the sooner you understand them; the earlier your photography will improve and become more predictable.

This is what will be covered in this guide:

There are those that believe that the manual mode is the only mode that a real photographer uses.

We don’t believe that. There are reasons that all of these different modes are available to photographers, even on the most professional level DSLR cameras.

Each mode has a purpose.

Are you ready to learn about them? Let’s go!

Photo Credit: Angela Fulks

By Peter Dam | Photography-Raw

Have you ever tried photographing dreamy landscapes in the daytime with smooth clouds? Then you know the challenges of getting the money shot with just one click.

But what if I tell you that you can achieve that perfect shot through photo stacking? Let’s find out more about what it is and what you can do with it when shooting long exposure photography!

The term stacking simply means combining several photos to create a “master image.”

There are several forms of stacking. The first one is called focus stacking. It combines several pictures with different focus points to create one final image that’s sharp from the foreground to the background.

The second type of stacking is for panorama. Instead of laying one image on top of another, it ‘stitches’ photos side by side to create a panoramic picture.

Finally, the third form of stacking is for long exposure photography which we will be learning today. It combines your image files to enhance anything from moving clouds to waves in the sea.

Each of the stacking methods we mentioned in this article involves a two-step process. The first part is taking a series of pictures, ideally in RAW format.

And the second part is combining them in post-production. The ideal editing suite for this purpose is Photoshop, and that’s what we will be using this tutorial.

When doing long-exposure photography, a lot of problems can easily ruin your shot.

A lot of things can quickly go wrong with an exposure time around 4 minutes. You could encounter all sorts of issues from false light to camera shake. Not to mention vignetting and image noise (hot pixels, thermal noise)!

But by dividing the shot into several shorter exposures, you can overcome most of the issues. You can stack your files together in Adobe Photoshop to achieve that one perfect shot.

Photo stacking is not a technique for every situation. But sometimes stacking your long-exposures is the only way to get a good shot. It’s imperative to know when you need it during shooting.

At night when the light is limited, you can do 2 or 4 minutes exposures without using neutral density filters.

But during the day, you’ll often have too much light available for long-exposure photography. Using slow shutter speeds in the daytime with a ten-stop ND-filter might still result in an overexposed shot.

Also by narrowing down aperture too much you can encounter problems because of diffraction effect (mostly over f/16).

Photo stacking your daytime long-exposure photos ensures you get correctly exposed shots. You’ll find this especially useful if you don’t own a ten-stop neutral density filter or more.

Besides false light, shaking is the most common reason for failed shots in long-exposure photography.

Since your camera shutter stays open for a few minutes, any movement it records will register as light streaks or motion blur. That’s the same reason why clouds in the sky or the waves in the ocean look wispy.

But small vibrations can also cause motion blur in your camera. Even a breeze or a gentle nudge could easily ruin your shots.

So remember to take the camera strap off your camera while shooting long-exposure. It acts as a sail in the wind and causes shaking to the tripod and camera.

You should also make sure the ground is sturdy enough to support your tripod. Use a remote trigger or self-timer for hands-free operation. Remember that even touching the shutter button could quickly introduce motion blur.

Of course, we also need to factor in all the unforeseen hiccups that can ruin a great long-exposure shot.

Regardless of whether it’s daytime or night, another common mistake is merely forgetting your remote. Without it, you can only safely go up to 30 seconds, which is the longest exposure time your camera allows.

Bulb mode without a remote requires that you press the shutter all the time. And that’s definitely a no-go if you want to avoid camera shake.

So before you venture out, make sure you have all the equipment you need. In this case, a tripod, ND filters, and your remote trigger will be necessary.

To avoid user error, you should also practice this taking long-exposure images before doing a big project. Becoming familiar with the process allows you to avoid mistakes and even troubleshoot issues.

We learned a lot about the various issues you may encounter when doing long exposures. Now the question is: How do you take photos for stacking?

In this section, we’ll show you how to do it on the field and how to blend the exposures afterwards in Photoshop.

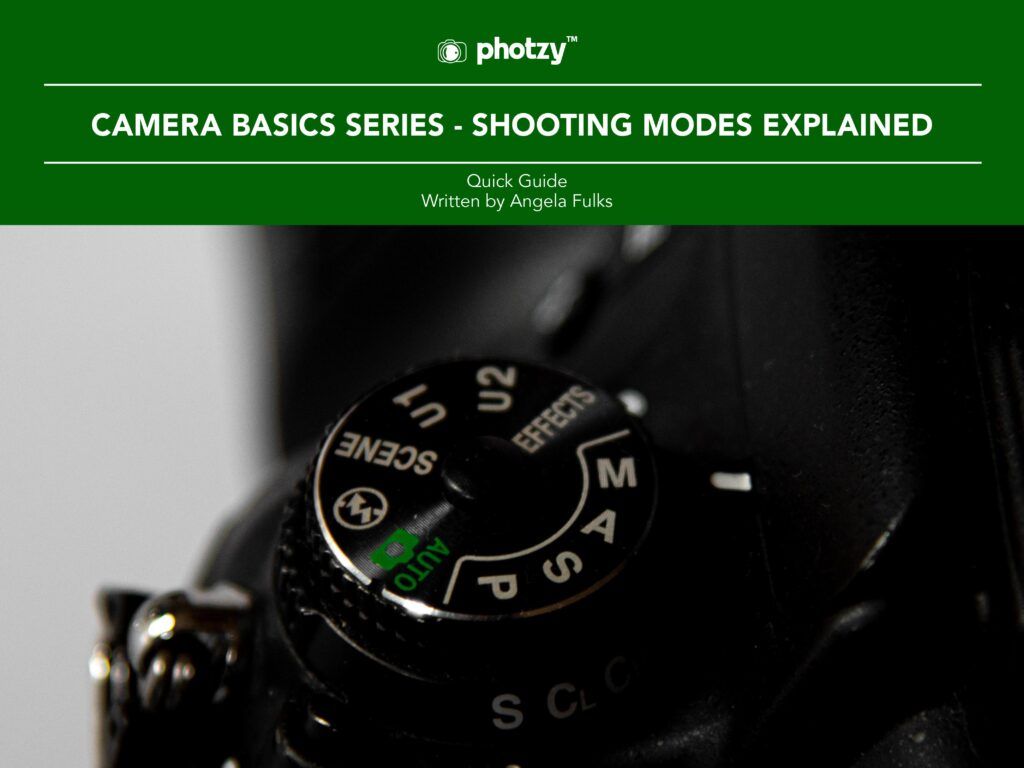

At the location, set up your gear as usual. Make sure your camera settings and ND-filters produce the correct exposure. Your histogram should peak just over the middle to the right when using an exposure time of 30 seconds.

To get the effect of a 4-minute shot, aim for eight good shots, each at 30 seconds (8 x 30 seconds = 4 minutes).

Feel free to take a few test photos to ensure you get the best exposure. Even though you’re stacking pictures, it would help a lot if all the shots you have are usable in the first place.

Get some extra exposures just in case some of them get blurred due to camera shake from a sudden wind gust or bypassing bus. You can leave out a particular shot from your sequence in the photo stacking process.

As you can see, the first part of this process is quite simple. If you’ve done long exposure photography before, this isn’t any different.

The part that you’ll need to learn is how to combine all those pictures in Photoshop. Now, let’s go through the process below.

Processing your set of daytime long-exposure shots is relatively easy.

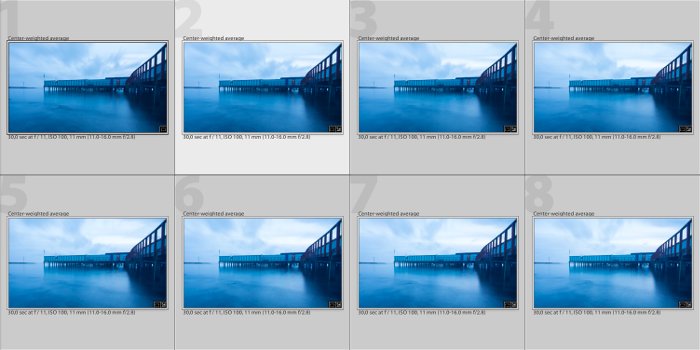

From Lightroom, open up your set of shorter long-exposures as layers in Photoshop. You do this in Lightroom’s grid-mode by selecting all the images you want to combine into one exposure.

Right-click and choose Edit In → Edit in Adobe Photoshop.

Don’t select Open as Layers in Photoshop since it’s for focus stacking macro photos. This process is different.

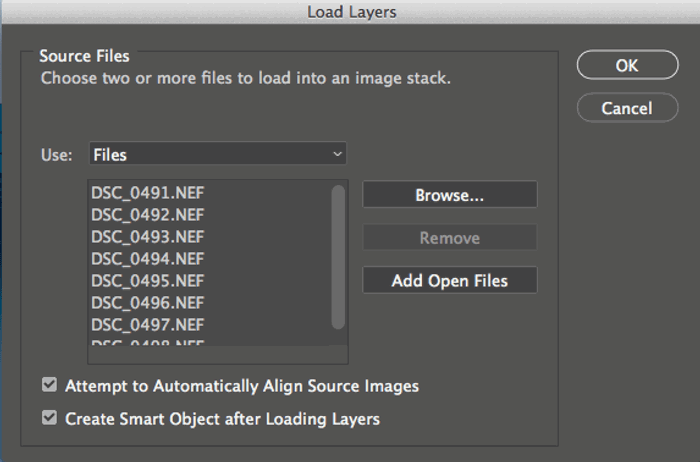

When the images finish loading into Photoshop, go to File → Scripts → Load Files into Stack.

In the appearing dialogue, choose Add Open Files to make the set of images appear under files to use for stacking.

Remember to check Attempt to Automatically Align Source Images and Create Smart Object after Loading Layers.

Click OK to begin the blending process. It usually takes some time for Photoshop to create a single Smart Object from all of the exposures.

Next, go to the menu Layer → Smart Objects → Stack Mode → Mean. Doing so makes Photoshop automatically blend the images in the stack into a smooth, long-exposure. The goal is to make it look like you took everything as a single long-exposure image.

At this point, you don’t need the layer to be a Smart Object anymore. Keeping it this way would prevent you from using a brush tool, for example. You should convert it by right-clicking on the layer and choose Rasterize Layer.

Next, process the image as you would for a standard daytime long-exposure or any other image. To get the best results, use selective sharpening of the areas in your photo that are not moving.

Long-exposures taken during daytime often have a lot of large white spots with clouds or silky soft water. Applying sharpening to these areas can cause an unwanted grainy look.

In this particular shot, I had to put my tripod halfway into the water to get the composition I wanted. But it resulted in a blurry 4 min. exposure. The small waves likely transferred a little shaking from the tripod to the camera.

However, by dividing the shot into eight exposures, I got several exposures that were usable for photo stacking.

Daytime long-exposure photography can give you some beautiful and creative results. But it requires patience and practice.

Using photo stacking can save you a lot of time and help you get awesome shots that otherwise might not be possible.

If you’re interested in more great photography ideas, Kindle Unlimited Membership Plans.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Photo Ephemeris helps you plan outdoor photography in natural light. It's a map-based Sun, Moon, and Milky Way calculator. Plan your shot with perfect precision.

“ One of the most useful apps for any nature photographer. ”

“ Head and shoulders above the crowd is The Photographer’s Ephemeris. Odd name, great app. ”

By Anton Gorlin

If you are into landscape photography, you might have already questioned your decision to wake up early for taking sunrise photography.

These are the times you should remember the joy of adventure and how rewarding sunrise photography actually is.

Read on to learn how to take sunrise photos that are worth waking up for.

A lot of people ask me “why sunrise, can’t I just do a sunset instead?” Of course, you can, but there is one massive difference between the two. And it’s an unbeatable argument in favour of sunrise for me.

When you photograph in the evening, there are lots of people around. They keep walking into the frame and distract you in so many ways.

During the sunrise, you get alone time with nature. You can focus on your thoughts and feelings and express yourself better. Also, the golden hour stays longer than the blue hour.

So, you have decided to do sunrise, and it’s time to prepare. I recommend getting ready the night before. This way, you’ll get an extra 10 minutes of sleep and you will also significantly reduce the chances of forgetting something important.

Do not forget to plan ahead and go with the right equipment.

Here is a list of sunrise photography essentials to pack in your backpack:

Everything else is either optional or depends on the scenery and weather.

As the saying goes, the best camera is the one you already own. This fact is true to some extent. So, if you already have a decent DSLR camera, invest in higher quality lenses.

If you are a new buyer, here are a few things to consider:

Your tripod needs to be sturdy and well-balanced. It should be able to hold your camera against the wind. If you go hiking, your only option to reduce weight is to get a carbon fibre tripod — but it comes at a cost.

I prefer Manfrotto and Slick tripods, they have always been great with zero issues.

However, you have a serious issue on your hand if you shoot seascapes and like to go into the water. It will probably ruin the tripod in a couple of months. If you’re photographing in an environment which ruins your gear, you should go for cheaper equipment.

I use Weifeng tripods all the time. They are cheap and provide excellent quality.

There are no strict rules about lenses, and you can get away with any focal length. Typically, photographers prefer wide or ultra-wide angles as their primary lens. I recommend having the whole range covered. Wide-angle + mid-range zoom + telephoto is an optimal choice.

If you are just starting out, you could get away with some general-purpose lens, like 18-105. With this type of lens, you will learn how to use different focal ranges and will know better what works for your style.

Here are a few recommendations:

APS-C:

Full Frame:

Sunrise photography is all about light. And, as we all know, light depends on the weather to a great extent.

You need to learn how to plan to get the best sunrise landscape shots. Typically, I prefer a partly cloudy sky. I wouldn’t bother with less than 30% cloud cover for a general sunrise landscape.

There are, of course, different scenarios. For instance, for a waterfall or a forest, I would prefer a clear sky to increase the chance of getting sun rays beaming through the trees.

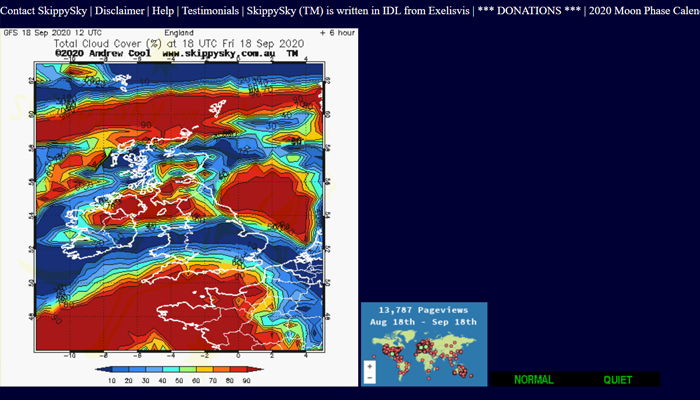

To figure out how early I have to get up, I use these two sites: The Weather Channel and SkippySky. The former has hourly cloud coverage, and the latter shows the type and thickness of the clouds.

SkippySky can look a little overwhelming, but you’ll figure it out fairly quickly. It also helps to predict if there is an opening between the clouds and the horizon. To get bright colors, you need high clouds. Low and heavy clouds rarely produce something spectacular.

All in all, you can never be 100% sure about weather conditions and have to try it out to see if it works.

The wind can also affect certain types of landscapes. For instance, don’t go to the cliff’s edge if there’s a strong wind.

Foggy weather can also play to your advantage — photographing a forest covered in fog will produce unique and dramatic-looking images.

I usually start by looking at Google Maps. I use the query ‘*area name* sunrise’, or something similar.

Once I find some East-facing area (North-East and South-East also work), I look for photos in Google Images, 500px, and other sites, which include a location. This search gives me a general idea of what to expect from the area.

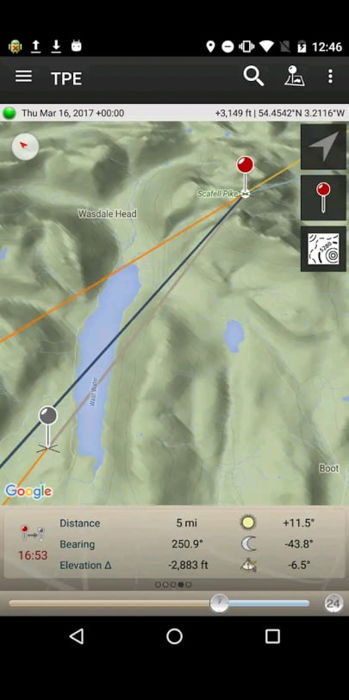

The Photographer’s Ephemeris app is also helpful for checking a location. You will see how light falls on a chosen spot almost anywhere on Earth.

The best way to prepare for the new area is to scout it before the sunrise. In the darkness, it could be hard to find a path, measure distance or see potential shooting spots.

So, if you get a chance, walk around the day before, take notice of the best places. Use some virtual reality app like Photopills or PlanIt! For Photographers to see the Sun/Moon/Milky Way positions for your future shots.

Typically, you need to arrive well before the actual sunrise for several reasons.

First, you’ll have the ability to shoot the long exposure. Second, you’ll have some time to get your equipment ready.

The first light appears about 30-40 minutes before sunrise, but you can start creating long exposure photos even earlier than that. I’ve seen clouds painted red 60 minutes before dawn. Keep in mind that all faint colours will turn vivid and juicy on the final shot.

There are a few ways to focus your camera in the middle of the night, but the easiest way is to use your headlamp or a torch.

Pick an object around the hyperfocal distance, then lock the focus and shoot.

These are the steps you need to follow:

Be sure to change back to the Autofocus mode once you zoom in or out because of the so-called focus breathing effect.

The pre-dawn period works best for long exposures, and that’s the main reason to come early. The longer the exposure time, the more movement you can catch.

Typically, in the total darkness, 60+ minutes before sunrise, you could get a shutter speed anywhere from a couple of minutes for f/8 to 10 minutes or more for f/16.

Use your judgment and the sense of beauty to figure out how long you need to expose the photo for. The most common subjects for long exposure sunrise photography are clouds and water.

This is the time when using a neutral density filter is crucial. They reduce the amount of light that is hitting the camera sensor, thus making it possible for you to shoot long exposure without overexposing the picture.

For the sky, you can expose as long as you like and the clouds will just turn into trails. For water, it is not as simple. Relatively calm water (river, lake) just smooths out with time and becomes perfectly flat at 30+ seconds.

Restless water, like the sea or the ocean, can turn into a foggy substance.

You can find a lot of useful tips on how to shoot long exposures in our course Infinite Exposures.

If you only take long exposures, you are limiting yourself with just one technique. By shooting short exposures as well, you can freeze an interesting motion in time.

My best advice here is to keep experimenting, keep trying different approaches and styles.

Photographers must understand light, appreciate it and work together with it trying to take all the best out of it.

For instance, you have envisioned a photo, and the light is entirely different. Don’t be stubborn! Be flexible instead, adjust to the lighting conditions and act following the current state of nature. Learn to quickly change the whole course of the morning and adapt to the environment.

It’s best to photograph with the light source on the side or in front of you. The sun behind the photographer is the worst case as it fills in and hides all the details and textures.

You’ve probably seen those starburst rays coming from the sun. It’s hard to believe how easy you can achieve just the same effect. Without going deep into the theory and the structure of aperture blades, below are a few steps to create a starburst effect.

Make sure you clean your lens properly, otherwise you’ll get ugly flares, which are hard to deal with in editing.

Golden hour is a period of the best light. It starts right after sunrise and lasts for about an hour. Usually, it’s warm, bright, and casts long shadows featuring all the textures.

It’s best to photograph with the light source on your left or right so that the shadows are the longest and the land features are most prominent.

For sunrise photography, you need a solution that fixes the difference between land and sky exposure. The sky is typically much brighter, and it results in either an overexposed sky or an underexposed land.

To alleviate this issue, you have two options:

Personally, I prefer the latter because filters have some disadvantages. First, they may have a color cast. Second, you need to carry a whole bag of filters. Third, it takes time to change the filter, and you may lose the moment.

To learn more about how to use bracketing in photography, check out our article here.

As with any other type of landscape photography, you typically shoot in either Manual mode or Aperture Priority mode. For landscape, you need a depth of field covering as much area as possible. That’s why you set the aperture to at least f/8 — but I recommend to go with f/11-f/16.

Don’t go higher than that because you will start losing sharpness instead due to lens diffraction. In fact, some lenses start to get diffraction even at f/16. You’ll need to test and compare.

The shutter speed is a variable here, and it depends on the surrounding conditions. When you just start shooting 60 minutes before sunrise, the shutter speed at f/8 could reach 5-8 minutes easily.

Pro tip: To get shutter speeds longer than 30 seconds you would need either a release cable or remote control for your camera. Set the camera to Bulb mode, then fire the button and then press it again once the time lapses. The other way is to use the Wi-Fi module that appears in some modern cameras.

As the ambient light becomes stronger, the exposure time decreases gradually. You need to learn what shutter speed you need for specific objects to make them look great and then adjust your settings accordingly.

Every camera handles ISO differently, so it requires an experiment to determine the max ISO you can get away with. Please note that darker photos with high ISO will produce much more noise than adequately exposed pictures with the same ISO level.

In fact, you only need to manipulate ISO for the sunrise when there are some moving objects, like waves or birds. In all other cases, you can keep it at 100. I also recommend to keep it as low as possible for the long exposures because otherwise, it would produce a lot of extra noise.

Sunrise is the most magical time of day when you can fully connect with nature. Even though there are many things you need to pay attention to, the magical atmosphere you can capture is always worth the effort.

Set your next alarm clock early and try it out! The tips above will help you to take stunning sunrise photos.

White balance and color balance are intrinsically linked in the digital photography process.

When you adjust the white balance settings within your camera, you’ll also be able to control the color balance within your image in post-processing.

Essentially, color balance is the post-processing extension of the white balance camera function.

However, the white balance can also be changed in post-processing when the original camera file is raw. So there are differences between the two.

This guide will look at white balance and color balance, how they both work, and their differences. Here’s what we’ll cover:

Grab your copy now!

Photo Credit: David Zawita