Civil rights photographer Tom Lankford dies of COVID-19

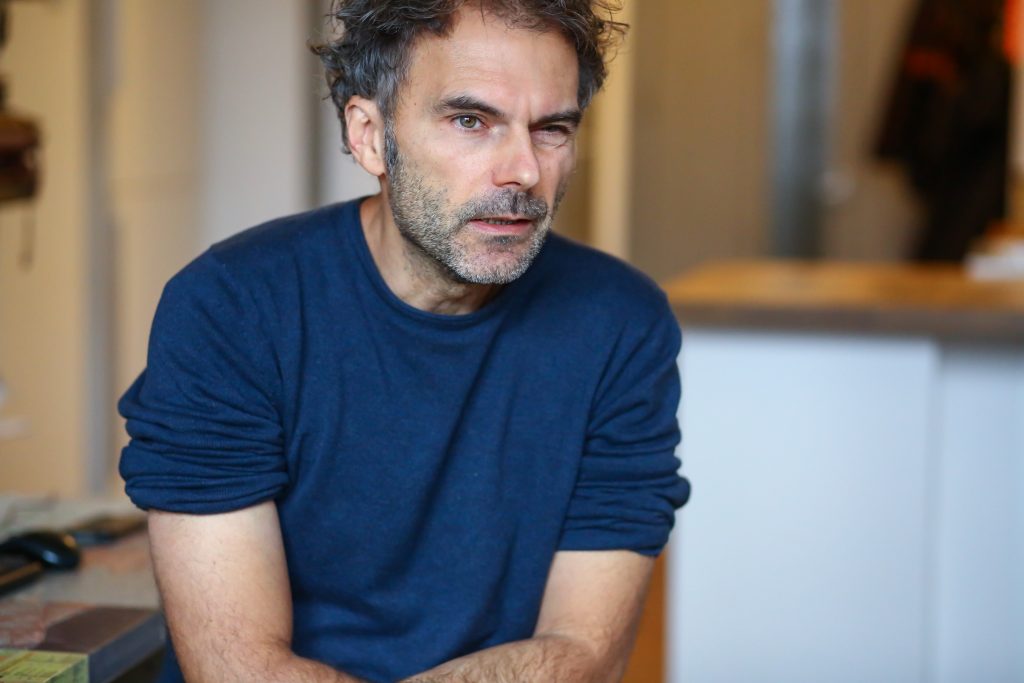

As a reporter and photographer, Tom Lankford covered many of the important events of the civil rights movement in the 1960s in Alabama, taking pictures of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preaching in Birmingham in 1960 and future U.S. Rep. John Lewis leading marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on "Bloody Sunday" in 1965. (Photo by Dawn Bowling)

A former Birmingham News photographer, nationally honored for documenting the civil rights movement, has died.

Tom Lankford died on Dec. 31, 2020, of COVID-19, pneumonia and heart failure, said his daughter, Dawn Bowling. He was 85.

When U.S. Rep. John Lewis died last year, Lankford’s photos of Lewis leading marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965 were among the most widely republished photos of Lewis. Lankford took pictures of the “Bloody Sunday” beatings of Lewis and other marchers in Selma on March 7, 1965.

In 2009, the Anti-Defamation League honored 12 former Birmingham News photographers including Lankford in the Concert Against Hate at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., with actor Liev Schreiber as master of ceremonies.

Among Lankford’s many historic black-and-white photos are several of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking at Men’s Day at New Pilgrim Baptist Church in Birmingham on March 6, 1960. King had recently resigned as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, where he led the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to spend more time on civil rights activism.

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks at Men’s Day at New Pilgrim Baptist Church in Birmingham on March 6, 1960. King had recently resigned as pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, where he led the Montgomery Bus Boycott, to spend more time on civil rights activism. (Photo by Tom Lankford/The Birmingham News/File)Alabama Media Group

As both a reporter and photographer for the Birmingham News, Lankford covered attacks on the Freedom Riders in 1961, the marches led by King and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth in Birmingham in the spring of 1963, the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on Sept. 15, 1963, the marches in Selma in 1965 and other civil rights events throughout the 1960s. Lankford reported on the final arrest of King in Birmingham on Oct. 30, 1967, when Major David Orange and Lt. Dan Jordan of the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office arrested him at the Birmingham airport on an outstanding warrant and took him to the Bessemer jail.

Lankford graduated from Hokes Bluff High School in 1953, then earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in journalism from the University of Alabama, where he was editor-in-chief of the student newspaper, The Crimson White, in 1958. He began working for The Birmingham News in 1959.

After covering the civil rights movement from Birmingham throughout the 1960s, Lankford later served as editor of the Huntsville News until 1977.

“That man was present for almost all the historical civil rights events,” said former Birmingham Police officer Teresa Thorne, author of the upcoming civil rights history, “Behind the Magic Curtain: Secrets, Spies, and Unsung White Allies of Birmingham’s Civil Rights Days,” set to be published April 20.

Lankford shared his experiences with Thorne for her book, including his controversial role as a “spy” for the Birmingham Police Department, recording civil rights meetings, wire-tapping King’s phone at the Gaston Motel and sharing intelligence with police.

“He was embedded with the police department,” Thorne said. “By his own admission, he became too involved and too close for an objective journalist. He did not regret it one bit.”

Although he was at times used by Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor, Lankford also did a secret recording of Connor in 1962 that helped defeat Connor and led to a new mayor-council form of government in 1963, Thorne said.

“He got wind of a meeting in the fireman’s union hall across from city hall,” Thorne said. “That was the famous meeting where they promised a pay raise to the firemen. He recorded it. It was used by people supporting a change to a mayor-council government.”

Earlier, he took a photo of former district attorney Tom King shaking hands with a Black man that was used as campaign propaganda by segregationist Art Hanes, who used it to help win the mayor’s race against King in 1961.

When events unfolded, Lankford always seemed to be there.

“For him, it wasn’t about playing politics, it was about getting the story,” Thorne said. “He did that by means we wouldn’t hold up as objective journalistic methods.”

Lankford once pretended to be a student at the University of Mississippi to get the first photograph of James Meredith, the first Black student at Ole Miss, sitting in class in 1962, Thorne said.

Lankford was threatened with violence by the Ku Klux Klan after a mob beat up Freedom Riders in 1961 at the Trailways bus station in Birmingham. They dragged him into an alley and demanded the film from his camera, which he gave up. But Lankford then went to Carraway Hospital and took what became famous pictures of Freedom Rider Jim Peck, one of those beaten up at the bus station, Thorne said.

“He had a lot of respect for Martin Luther King Jr. and Fred Shuttlesworth,” Thorne said. “He admired their courage. He was on a friendly basis with them.”

Few people had such access to both civil rights leaders and the inner workings of the police department that enforced segregation.

“It wasn’t that he believed in Connor’s racism,” Thorne said. “He did it for the purpose of getting a story and having access.”

Bowling, one of his two daughters, said her father cultivated close friendships with law enforcement officers “so he would always have the relationship he needed,” to get a story or picture.

“Daddy had very close ties with the police department, state troopers, the sheriff’s department and the FBI,” Bowling said. “One of his best friends was Sheriff Mel Bailey,” who was sheriff of Jefferson County from 1963-1996.

In the end, Lankford got pictures that became an important part of the historical record.

“He was a complex man, and it was a complex time,” Thorne said.

After his newspaper career, Lankford worked in public relations for the Parson/Gilbane Joint Venture and Dravo Utility Constructors, then Saudi Arabian Parsons Limited, as a liaison with the Saudi Royal Commission during construction of the city of Yanbu. He worked for the Saudi Royal Commission from 1987-99.

He lived from 1981-1999 in Saudi Arabia, and sometimes made presentations to Saudi princes in the desert under tents on Persian rugs set on the sand, said Bowling.

He returned to Hokes Bluff and began gardening, but then decided he wanted to be a cross-country truck driver, Bowling said. He and his wife of 35 years, Tan, whom he had met in Thailand, both got certified as commercial truck drivers. After several years of driving 18-wheelers from Alabama to California, with his wife and their golden retriever, he had a heart attack in 2008 near the U.S.-Mexico border.

He gave up truck driving, but in recent years had become a greeter at the Sam’s in Oxford. He always wore a tie and dress shoes, as he had during his newspaper days, and struck up conversations with customers coming into the store.

He gave up his Sam’s greeter job in March 2020 when coronavirus lockdowns began. “He was a dapper dresser, always wearing a tie,” said Bowling. She recalled that when her parents divorced in the early 1960s, Lankford would pick up her and her sister, Carrie, for the weekend and take them with him as he worked.

“He was very tall, had these long legs, walked really fast, and he always had a camera on his shoulder,” she said.

She recalled one time he had taken pictures of the Ku Klux Klan at a meeting, and asked them to take their hoods off. “He stood on the back of a pickup truck and they posed for him with their masks off,” she said. “Then they changed their mind. They came to the house and demanded Daddy’s camera. They searched the house and found it in the crawl space. They tore up his camera and took his film.”

See the obituary here.

Albert Turner and Bob Mants are walking directly behind Williams and Lewis. (Photo by Tom Lankford/The Birmingham News/File)Alabama Media Group

Share this article.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

PHOTOGRAPHY FREEBIE:

How to make money with your Photography even if you're not a Pro.

Copy & paste this link into your browser, click ENTER, and enjoy:

https://mrdarrylt.blogspot.com/2020/01/how-to-make-500-month-from-your.html

or

https://www.photography-jobs.net/?hop=darryl54

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Visit me on Facebook and post your pictures.

https://www.facebook.com/Darryl-T-363867387724297/