When and how to Photograph

1. “When in doubt, click.”

One of the biggest regrets I often have in my photography is not clicking the shutter.

For example, I might see a good scene, but I might hesitate. I let fear get the best of me.

For example, I get worried if the subject might get angry at me. I get worried if the photo I am taking is a “cliche” photo. I worry about my technical settings, focusing, and the light.

However my suggestion is whenever your heart tells you, “Take that photograph!” — listen to that voice.

Don’t let your brain and rational mind dictate your shooting style. Let your gut, intuition, and emotions control your shooting process.

2. Be selective about what you decide to photograph; but once you find something good, shoot the heck out of it

One of the biggest lessons I wish I knew if I started photography all over again is this — to be more selective about the scenes that I find interesting. But once I find a scene that is interesting, take as many photos of that scene as humanly possible.

For example, when I started photography, I took 1–2 photos of everything I saw in a day (around 300 photos). However often none of these photos were interesting.

However I recommend doing the opposite — only look for 1–2 interesting situations or scenes or “photo opportunities” in a day. Once you find that situation, then take 300 photos of each of those scenes/situations.

Why is this a better tactic?

In photography, it is rare that we find a good scene which makes us excited, and our hearts beat. Once that moment is gone, it is gone forever.

So once you find that scene that really speaks to your heart, “work the scene” and take as many photos of the scene as possible. That can be 3 photos, 5 photos, 10 photos, 30 photos, 50 photos, or even 300 photos.

The difference between beginner photographers and master photographers is this — the beginner photographer is satisfied with “good enough.” The master photographer seeks perfection.

3. Big cameras are overrated

One of the big myths in photography is that the bigger your camera, the more “professional” you are, and the better photos you will take.

I take the opposite approach — I say that big cameras are overrated, and small cameras are underrated.

I am a huge fan of small and compact cameras, because the smaller your camera, the more likely you are to take it with you everywhere you go, and the more likely you are to make photos.

In my personal photography journey, I started off with a small Canon digital point-and-shoot camera. It fit in my front pocket, and was easy for me to take it with me everywhere I went.

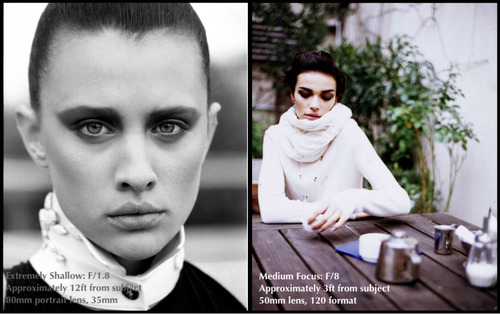

However as time went on, I wanted to make more “professional” photos that I saw online. I saw people shooting with photos with shallow depth-of-field (later figure out this was “bokeh”) and I was enamored. I invested all of my meager savings into buying a Canon 350D (Rebel XT), and soon got suckered into buying a “full-frame” camera (Canon 5D) or else I wouldn’t be taken as a “serious” photographer by others.

The problem was as I acquired more gear, the bigger my camera got (and the lighter my wallet got). And the bigger my camera became, the less likely I was to carry it with me everywhere I went.

I used to carry my point-and-shoot camera with me constantly in my front pocket, and and it brought me so much joy — because I was making photos constantly. Once my camera got too big, it started to collect dust on my shelf. I would never take it with me, because it was too much of a bother.

If anything, the ideal camera to shoot with is a smartphone. Why? It is small, invisible, and always with you. Sure the image quality isn’t as good as a high-end digital camera, but I feel the trade-off is worth it.

If anything, photographers focus too much on the quality of a photograph in terms of sharpness. They never focus on the quality of a photograph in terms of emotion and composition.

So when in doubt when buying a new camera remember: the smaller the better.

4. Don’t “take” photos, “make” photos

Probably the biggest breakthrough I made in my photography is when I learned the difference between America and Europe — Americans usually say “take” photos, while Europeans tend to say “make” photos.

What is the difference?

For me, “taking” a photo implies you are stealing something from someone. It sounds forceful, aggressive, and unfriendly.

Whereas “making” a photo implies you are collaborating with your subject, that you are making art, and you are doing something altruistic.

Even as a tip, whenever I approach strangers that I want to photograph, I will ask them, “Excuse me sir, do you mind if I made your photograph?” (instead of asking them to “take” their photograph).

Generally this question gets a lot better response. Why? Because it implies that I want to work with my subject to make something artful.

A small change in terminology can drastically change how you approach photography, creativity, and collaboration as a photographer.

5. Focus less on technical settings; focus more on composition and framing

One of the regrets I have in my photography is worrying too much about technical settings, trying to master “manual” mode, and trying to brag how all my photos were shot fully-manual.

I do believe that having some technical knowledge of photography is important— it can help you make the photos that you want to make.

However knowing technical settings for the sake of knowing it is a bit of a waste of time. Furthermore, if you can use an easier camera setting that creates the photos you desire, go for the easier route.

If you have an exhibition, nobody will care whether your photo was shot fully-manual or in a more automatic mode. What matters more than technical settings is emotion, soul, and creativity.

6. “Set it and forget it”

I’m a big fan of using “P” (program) mode in photography.

Why?

99% of the time when I am shooting in “P” mode, I get the photos I want.

To take it a step further, I try to simplify my technical settings as much as possible in my camera. For my ISO I set it relatively high (ISO 800–1600) which prevents me from getting blurry photos. As for autofocus, I just use the center point, which tends to be the quickest and most accurate.

While these aren’t the best settings for every situation, they work for 99% of the situations for me (especially when shooting street photography).

I think that the less you have to worry about your technical settings, the more mental energy you will have to focus on composition, framing, and capturing emotions in your photographs.

Furthermore, if your camera can make your life a little easier— why don’t you let it? Insisting on shooting fully-manual for the sake of it on your camera is like insisting only on sending handwritten letters (and never using email).

So once again, with technical settings— think of the classic American Rotisserie Chicken commercial: “Set it and forget it.”

7. What you subtract from a frame is more important than what you add to a frame

Having a good composition in photography is more about what you decide to subtractfrom the frame, rather than what you decide to add to the frame.

For example, many beginner photographers have the issue of making a photo that is too cluttered. Not only that, but they are generally too far away from their subject.

So instead of trying to add more information to your frame, seek to subtract distractions, noise, and superfluous elements.

If you are a beginner photographer, the best composition advice I can give is to start off with a simple background. Start off by looking for a white, grey, or neutral background if possible. Then add in your subject.

Furthermore, focus on framing by looking at the edges of your frame. If you have clean edges in the frame of your photograph, the less likely you are to have a poor composition. And the less likely you will need to crop a photograph.

So the next time you’re making a photograph, think to yourself: “Is this element in my frame adding or distracting to my image?” When in doubt, subtract from the frame.

8. The most important question to ask yourself in photography: “Why do I make photos?”

The common questions we are asked in photography include:

- What camera do you shoot with?

- What lens do you have?

- What do you like to take photos of?

Very rarely do people ask us, “Why do you make photos?”

The why of photography is probably the most important question you will ask yourself.

To start off, ask yourself these questions:

- Why did I first pick up a camera?

- Why did I first start taking photos?

- Why does photography bring me joy?

By answering these questions, you will better discover who you are as a photographer and human being.

One of the lessons I’ve also learned in photography is that the point of photography isn’t to become a great photographer. The point of photography is to enjoy your life.

Photography should be a tool which enriches your day-to-day life, and your living experiences. If photography becomes a chore or a burden to you, why do you make photos?

And once you figure out why you make photos, you will have a better insight in terms of what camera to shoot with, what to make photos of, and how to share your photos.

9. Buy books, not gear

I’ve spent thousands of dollars on camera equipment over the years. I regret about 90% of my purchases.

However I’ve also spent thousands of dollars of photography books over the years. I regret 0% of my purchases.

Any camera you buy today will be redundant or outdated in about 5–10 years.

Any photography book you buy today will probably still be relevant 5–10 years from now. If anything, many of your photography books (if you buy art books) will increasein value.

The mistake I made in photography is that I thought my photos weren’t good enough because my camera wasn’t expensive enough. I thought if I bought this new camera, this new lens, this new tripod, or whatever— I would suddenly become more “creative” and “inspired” in my photography.

The effect lasts a week, then you are back to square 1.

The only lasting effect to improve my photography was to invest in photography books — especially photography books from the masters of photography.

Think about it— a master photographer will probably spend his/her entire working life (30–50 years) to create a body of work. And that photographer will invest thousands of dollars to produce this book, market the book, and share it with others.

A photography book is a well-curated, well-considered, and well-edited collection of images. In today’s social media society, we are drowning in cat photos and selfies by sunsets. The more time we spend on social media, the more we are eating “visual junk food.”

You are what you eat. Therefore if you look at great photography (especially in the form of photography books), you will aspire to make great images. You will learn what makes a great photograph, what great composition is, and how to make a body of work that lasts through the years and decades.

Don’t get me wrong, I am still suckered by G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome). I still have moments where I doubt myself, and think by investing in a new camera system I will suddenly make better photos.

But in those situations when I have an urge to buy a new camera, I will spend $50 on a book instead. And that urge will go away, and I will be inspired to make greater photos.

Never forget, #buybooksnotgear

10. Photography workshops are a better “bang-for-the-buck” experience than attending photography schools

I have never been to photography school, but I have many friends that did. While they had a great experience, many of them are $200,000+ in debt.

Was it worth it? I don’t think so.

Honestly, all of the information you need about photography can be easily learned on the internet and YouTube. And if you want feedback and direction in your photography, it is much better to attend photography workshops or hire a photography tutor.

I attended a photography workshop by the Magnum photographers Constantine Manos and David Alan Harvey — and had nearly a decade-worth of photography knowledge from both of them in a week. I regret not taking one of their workshops earlier on when I started photography. I would have saved tons of time, money, and effort.

11. Aim to make 1 good photo a month, and 1 great photo a year

One of the biggest challenges I had in my photography starting off was how easily disappointed I was. I had the wrong idea that every time I went out, I had to make a great photograph.

However upon studying the work of the master photographers, I discovered that they rarely got good shots. The only difference between us and the master photographers is that they are more selective in terms of which photos to share (and which photos notto share).

Upon studying many master and contemporary photographers, most of them only admit to making 1 good photo a month, and 1 great photograph a year.

And think about it— if you can make 1 good photo a month, that is 12 good photos in a year. 12 photos is good enough for a nice little coffee shop exhibition, or website gallery.

If you make 12 good photos in a year, then in 3–4 years you can easily put together a photography book of 36–48 good images. You can either self-publish your work, or approach a publisher.

If you make 1 great photograph a year (depending on how old you are), you can aspire to at least make 5–10 great photos before you die.

I feel that if a photographer is even remembered for 1 photograph, he/she has done their job as a photographer.

And think about the master photographers from the past— very few photographers are remembered for more than 1 memorable shot.

So set your expectations low, but work hard. This way you will never be disappointed in your photography.

12. More megapixels, more problems

This goes back to the G.A.S. (Gear Acquisition Syndrome) point. We think our photos aren’t good enough, and we need better cameras with more megapixels, better sensors, etc.

However what I’ve discovered in my photography is this — more megapixels, more problems.

When you upgrade your camera, you often need to upgrade your lenses (let’s say if you’re going from a crop-sensor to a full-frame sensor). Not only that, but you will probably need to upgrade your computer (to handle the bigger megapixels of the files). And not only that, but you will probably need more hard drives or invest in more storage to house all your files.

Also consider— beyond a certain point (let’s say 8 megapixels) you don’t need any more. Unless you are a commercial, studio, or fashion photographer and plan on printing your photos as big as billboards.

An 8-megapixel photo is good enough for a quite big print (12×18 inches, or even 20×30 inches). And to be honest— 99% of our photos are just going to be shown on our mobile devices and computers. How many megapixels do you need to see an image on a 5–6’’ screen?

So nowadays, whenever I see cameras with more megapixels, I feel leery. I like to stick to cameras with fewer megapixels whenever possible.

Fewer megapixels = less stress = more time and energy to enjoy photography.

By Eric Kim