Where to start with film

For those that have taken up photography in recent years, film may seem like an ancient format that no longer serves a purpose. But I’m not going to spend the rest of this tutorial trying to compare film or digital photography in order to convert you! There are different techniques required, but much of what can be learned by understanding film photography can largely benefit your digital work. Even though I began my photography on digital, it was only once I picked up a film camera that I really began to understand the concepts of ISO, exposure, aperture and taking time to get the right shot!Film v. Digital

Although the preference of film or digital will always come down to the individual photographer, there are a few fundamental elements of film photography that I see as a distinct advantage over digital. With a film camera, you are doing all the work, you have to understand the physical process of the shot being taken and must have the correct exposure settings.There isn’t the option of clicking away, checking the LCD, and trying again. For me, this means I feel far more involved with the shots that I’m taking. I also know I’m not letting the electronic brain of a digital camera do all the work for me.

The Cost

There is also the cost to consider. Many people would assume that film photography is more expensive due to having to buy film and pay for processing, but a decent film camera will last a lifetime. My old Pentax SLR is way older than me, works perfectly and won’t go out of date.With digital cameras there is the almost yearly upgrade option. Manufacturers aim to ensure that you keep up with technology, have the most pixels, the newest features and the sharpest shots. Obviously these updates are beneficial, but they come at a price.

Film Formats

Film comes in a few different flavors suited for different purposes. The main types are black & white, colour positive (slide film) and colour reversal (or negative). The most popular size of film is 35mm film. Many single lens reflex (SLR) and rangefinder cameras use this film. It typically comes in rolls that allow for either 24 or 36 exposures.The two other major sizes of film are medium format film and large format film. Medium format film is much larger than 35mm film and requires a medium format camera. Medium format is regarded to be of higher quality than 35mm and is therefore still used by many professional photographers. It comes in 120 or 220 formats. Almost every medium format camera can use 120, as it has a paper backing. 220 does not, so only certain cameras can use it, but the lack of paper allows the roll to hold more film, twice as much to be exact.

Large format film is slightly different than both 35mm and Medium format film as it comes as individual 4′x5′ sheets (or ever larger) that have to be loaded into film holders. Each film holder must be loaded in the dark. Each holder also only holds two exposures. The traditional photographer’s vest with all the pockets was originally designed for large format users. You had to have a lot of pockets to hold all those film holders.

Types of Film

Once you’ve decided which film format you’re going to use, there are many different types of film to choose from. Aside from the types mentioned earlier, companies such as Fuji, Ilford, Kodak and Agfa all make a large variety of films. Each have different capabilities depending on their ISO, purpose of use, contrast and speed.An entire tutorial could be written about this topic alone, but before you rush out and buy loads of rolls of film, have a quick read up on the film manufactures website to work out which film best suits your needs. Also, try to avoid using the cheapest film; if you’ve got a good camera and you want to take great photos, then it’s worth using professional quality film.

Film Cameras

If you’ve taken an interest in the realm of film photography, you’ll want to decide on a film camera. Similarly to the world of digital photography, there are different cameras that suit different purposes. The most popular cameras are 35mm as I mentioned early. These cameras range from automated point-and-shoots to simple (but professional) rangefinder cameras to fully manual (or fully automated) SLR cameras.The next step up is medium format cameras, which are slightly bulkier, but produce larger and higher resolution shots. If you really want to start with the basics, you could even try out a Lomo or toy camera which are very trendy at the moment and are designed to be very easy to use.

Patience, Discipline and Getting Your Settings Right

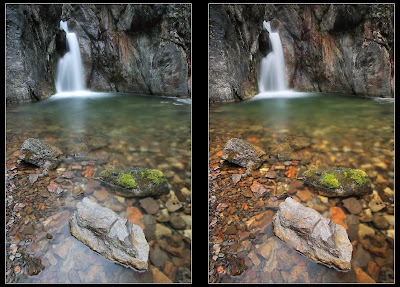

One of the major differences between shooting digital and film is that with film, you don’t have the option to assess your shots as you are working. For some of you, that will take a lot of getting used to. You’ll no longer be able to use the trial and error method of photography. As far as I’m concerned, this is not a bad thing.When shooting film, you need to take that little bit more time to ensure that your exposure settings are correct depending on the light available, for which a light meter can be very useful. You’ll need to check that you’ve got the composition just as you want it and that you’re happy with the shot you’re about to take. This all requires you to be very familiar with your camera. So be sure to read through the manual or spend time with your camera.

This discipline and patience means that a far higher percentage of the film shots that you take will be good quality shots and this practice has improved my overall photography significantly as I remember to take time over each shot and not just snap away hoping I’ll get the shot I want.

Developing

Once you’ve taken your shots, you’ll have to be patient before you get to see them. For me, that’s all part of the fun. When you decide to get your film developed, make sure you get it done properly. If you’re not confident with developing it yourself, or you don’t have the resources, take it to a store or studio to get someone to develop it for you.Remember that you’re trusting someone else to develop your shots, so take it to someone who you think will take care over developing your shots rather than paying a few dollars at the local mall. If you do get the chance, try and have a go at developing the shots yourself. This is a crucial part of film photography and gives you as the photographer far more control over what you’re producing.

Scanning and sharing

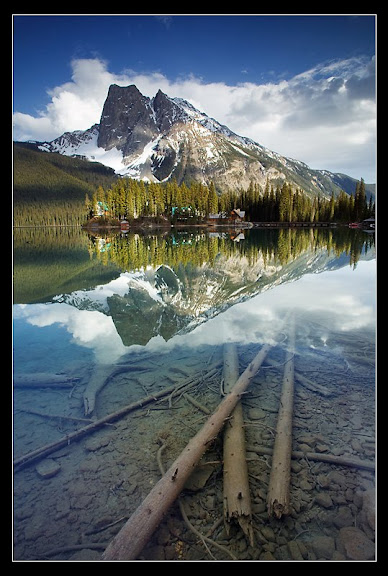

When you do have your prints, chances are you’ll want to get them onto a computer somehow. Some print stores will be able to put the photos onto a disc for you, but please don’t use this as an alternative to getting them printed out. It detracts so much from the whole process. It’s a great moment when you first get to look through your new prints.You then also have the option of scanning your shots into a computer, which is fine, but be aware that a low quality scanner will seriously diminish the quality of your shots. After scanning, you will be able to share your new beautiful film shots online and show the world how great they look. And don’t just leave the prints in a box somewhere!

Get Creative

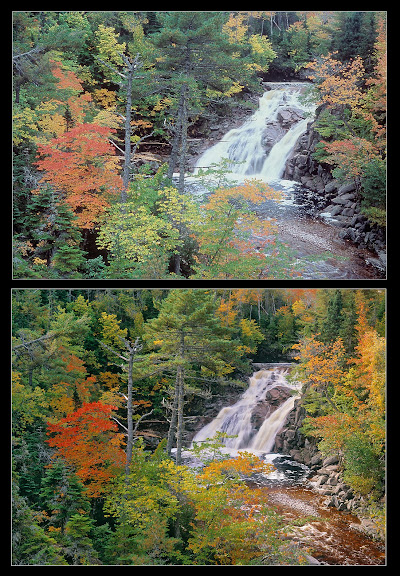

Now’s your chance to go out and give film photography a try. Hopefully you have a better understanding of what film photography is all about and that there is a lot to be learned and enjoyed. Try to get your hands on a film camera. Save up a few pennies and find one on Ebay or go and have a look around the attic at you mum and dad’s house.You can then head out on shoots with both your digital and film cameras and try out the different disciplines at the same time. Compare results and keep experimenting with film. You’ll soon be ready to try processing your own work!

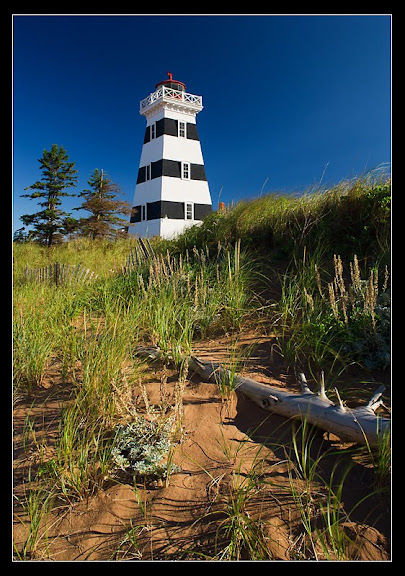

Are you already a film aficionado? Share links to your film images in the comments below. Let us know if you have a favorite film camera, and tell us your favorite film tips!

Article by: Simon Bray