When noted outdoor photographer and author Darwin Wiggett

writes about filters, he speaks from his own years of successful

experience. His series of stories featured on this blog have become a

trusted reference source for many visitors. Now Darwin reviews the basic

topic of polarizers, and offers us his personal perspective based on his own methods, experience and equipment."I

use a polarizer for almost every landscape and nature image I make,"

says Darwin Wiggett. "In fact, I always start off with a polarizer on my

lens. It's only if the filter has no effect -- or a negative effect

(which is rare) -- that I will take it off the lens. And if you think

you can replicate the effect of a polarizer in software, you can’t --

plain and simple. Below are my Seven Rules for using a polarizer.

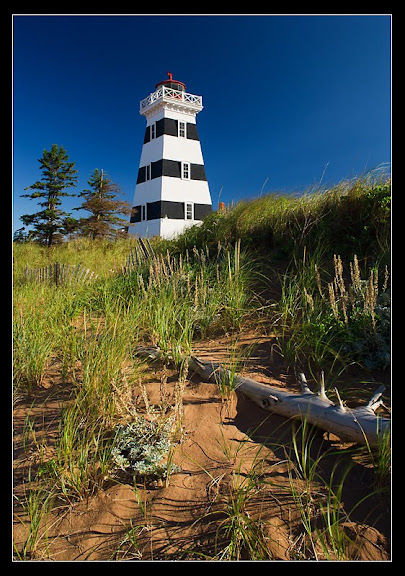

Rule 1: Use a Polarizer for Side-Lit Landscapes

"Whenever

I am shooting at sunrise and sunset and the landscape is side lit, a

polarizer will have an enormously beneficial effect. The filter reduces

the scattered light in the scene, effectively darkening the sky and

adding saturation to the ground elements by removing glare from the

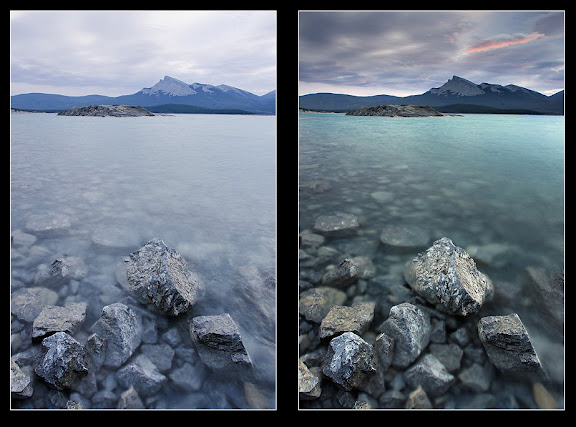

reflected highlights. Compare the two images in Photo 1. The left image

was taken without a polarizer and the right was taken with one (a

Singh-Ray LB Neutral Polarizer). The right image has more saturation of

colour in the foreground because the filter removed reflective glare.

The sky in the right-hand image is also more saturated and richer in

tone.

Rule 2: Use a Polarizer to Enhance Rainbows

"Any

time you see a rainbow, immediately slap a polarizer on your lens! Spin

the polarizer around and you’ll see the rainbow disappear totally and

then reappear with great intensity. Obviously you want to rotate the

filter to give you the best intensity in the rainbow. A rainbow is

polarized light so a polarizer either kills the rainbow or it pumps up

the colours enormously, depending on how you rotate it.

"As soon

as I saw this rainbow in Photo 2, I knew I had a winner. But by the time

I got my gear out and the composition set up, the rainbow was already

fading. To recover the intensity in the rainbow, I simply used my handy

polarizer. A side benefit to the polarizer is that it removed reflective

glare from the road and saturated the colour in the yellow line.

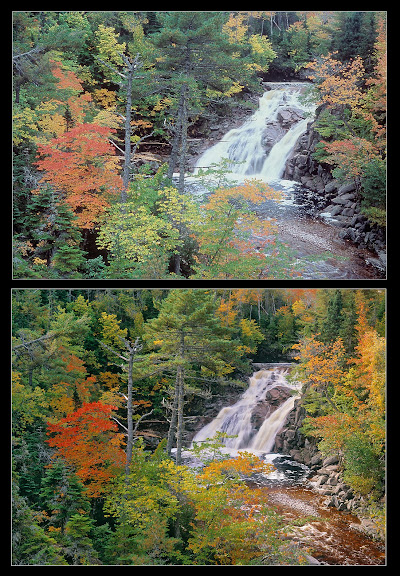

Rule 3: Use a Polarizer for Intimate Landscapes on Overcast and Rainy Days

"One

of the cardinal rules in landscape photography is 'in overcast light

shoot tight.' Bald white skies in a landscape photo really jar the eye

so most photographers concentrate on more intimate landscapes and

exclude the sky when it is overcast. A polarizer won’t darken an

overcast sky but it will eliminate reflective highlights off leaves,

rocks and water to help saturate the colours in the photo.

"Just

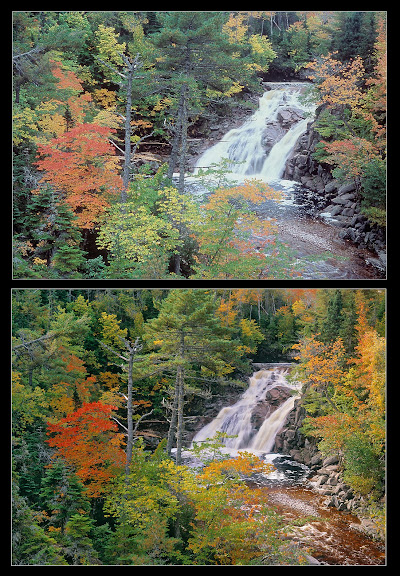

how much effect does a polarizer have on an overcast day? See for

yourself in Photo 3 (top image with no polarizer; bottom image polarized

with a Singh-Ray LB Warming Polarizer). I think you’ll agree polarizers

have their place on grey days!

"On

overcast days after a rain, it is even more important to use a

polarizer. When everything is wet, there will be a lot of reflected

light coming off the wet surfaces and this glare reduces the quality of

tones and colour. In Photo 4, I used a Singh-Ray LB Warming Polarizer to

supersaturate the colours. Who needs the hue and saturation slider in

Photoshop when you can capture colours this good in-camera?

"Many

people ask me why I use a warming polarizer when I could just change

the white balance on the camera to get the same warm effect. The warming

filter in the LB Polarizer is subtle -- just enough to offset the

effects of UV light -- and the result is a cleaner file captured

in-camera than if I just used a polarizer plus a warmer white balance

setting. The better the information captured by the sensor, the better

the final image. So on grey days, in particular, I always use a

Singh-Ray LB warming polarizer.

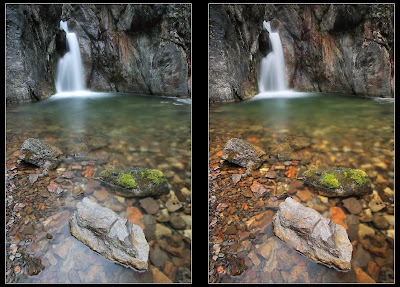

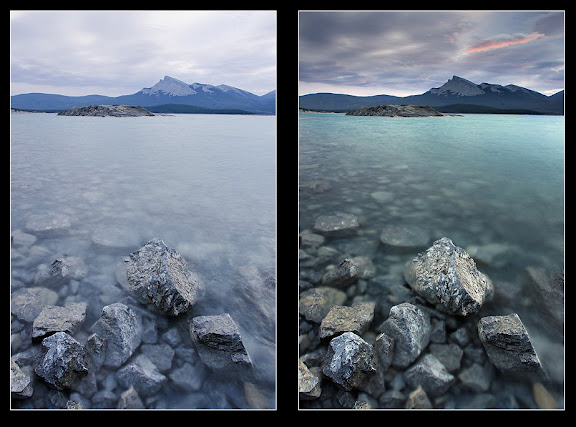

Rule 4: Use a Polarizer to Remove Reflective Highlights on Glass, Metal and Water

"If

you want to pierce through the reflective surface glare of water, see

through glass and remove the glare from metal, be sure to use a

polarizer. In Photo 5 you can see how the addition of a polarizer (right

side) gives you views underwater that are not possible in the

un-polarized photo (left side). With reflective surfaces, the reflection

is sometimes the most important element and sometimes the subsurface is

more important. Just rotate your polarizer until you see the precise

effect you like best.

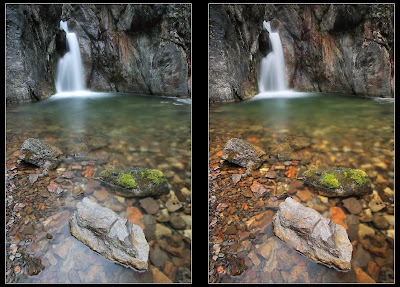

"In

Photo 6 the image is improved by using the polarizer (right side image)

because it allows the viewer to see the interesting rocks under the

water which could not be seen well in the non-polarized version (left

side image).

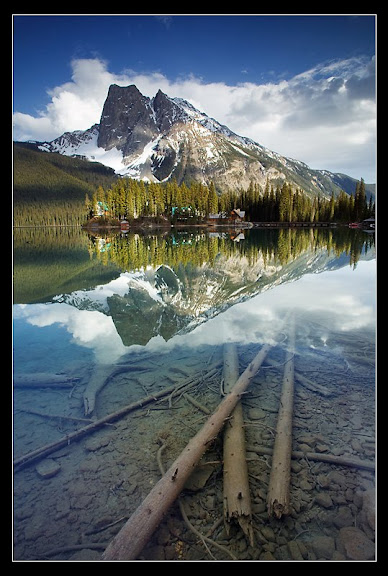

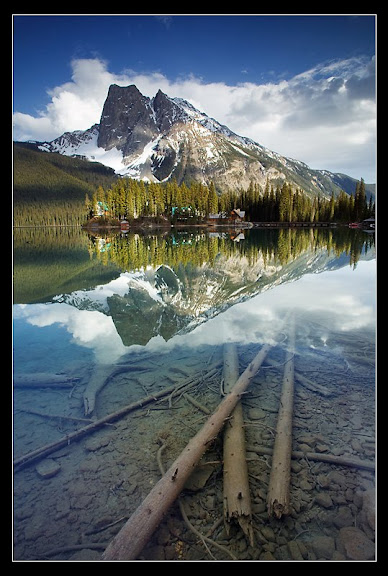

"In

Photo 7, my LB Warming Polarizer allowed my to reach under the surface

of the lake for my foreground interest. The polarizer not only let me

see underwater, it also darkened the sky above and increased the warm

colour saturation of the forest around the lodge. And it was all done in

the camera.

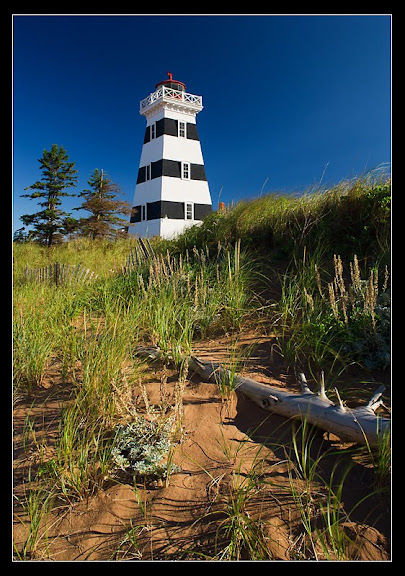

Rule 5: Avoid Uneven Polarization of Blue Skies When Using Wide Angle Lenses

"One

of the classic mistakes when using a polarizer is to rotate the filter

to create the maximum effect when shooting blue-sky scenes with

wide-angle lenses. In Photo 8 the upper center of the sky is much darker

than the rest of the sky and for some viewers this uneven polarization

is unacceptable. There are several solutions to this problem. Sometimes

just rotating the filter slightly will reduce the uneven effect. Often

if you move back a bit from the scene and use a little longer focal

length setting on your zoom lens you will take in less sky and thereby

reduce the problem. And finally you can make two exposures of the same

scene, one with the polarizer rotated to maximum for the greatest

benefit to the foreground and one exposure with the polarizer turned to

minimum effect for a more even, ‘natural’ sky. Then you can blend the

two exposures together in Photoshop.

Rule 6: Combine an ND Grad Filter with a Polarizer for the Ultimate in Contrast Control

"One

of the major hurdles to leap over in landscape photography is the

problem of high contrast between the sky and the land. In many cases

skies are so much brighter than the landscape that if we expose properly

for one, the other is either washed out or is too dark. In Photo 9, the

image on the left was made without any filters. Notice how the sky is

overexposed without detail and how the water has a pale ghostly sheen.

By adding a Singh-Ray LB Warming Polarizer, I not only removed the sheen

from the water (caused by reflective glare and UV haze) but the

polarizer also allowed me to see the underwater rocks much better and

added colour saturation to the above water rocks (right image). The use

of a 2-stop hard-edge

Graduated Neutral Density

filter over the sky and mountains darkened this overexposed area of the

image revealing all the detail that was there that day. Whenever I have

a bright sky in a landscape scene you can bet I’ll pull out both my

polarizer and my grad for contrast control. To understand how to stack a

grad and polarizer together see my previous blog article:

Filters, holders and vignetting: building a filter system that works with your lensesRule 7: Combine a Polarizer with a Solid ND Filter or use the Singh-Ray Vari-N-Duo for Creative Motion Effects"One

of my favorite techniques in nature photography is 'Painting with

Time.' This technique is created by combining a polarizer with a

solid ND filter

(e.g. 5 f-stops or more) to create long exposures to record movement in

nature. Anything that moves -- rushing water, swaying grass, flitting

clouds -- takes on a surreal, painterly look when recorded with a long

exposure. The polarizer gives all the benefits we have seen with the

filter (reduced glare, increased colour saturation) while the solid ND

filter allows us to record nature’s movement over time.

"Often I like to use the Singh-Ray

Vari-N-Duo

because it is a polarizer and variable solid ND filter (2-8 stops)

built into one convenient filter. But you can also use filter holders to

combine a polarizer and a 5-stop solid ND filter like I described in

Filters, holders and vignetting. To learn more about other benefits of using a polarizer, a grad and a solid ND filter together see

The Terrific Triple Threat.

"Remember

when you use a polarizer and a solid ND filter together -- or if you

use the Vari-N-Duo -- that your exposure times will be long (from 4

seconds to several minutes), so a solid tripod and cable release are

mandatory. There are other things to consider in terms of getting proper

exposure and I cover these in detail in my

Paint with Time download for anyone interested in detailed specifics.

"In

Photo 10, the left side image was taken on a windy day using a

Singh-Ray LB Warming Polarizer to get a better colour and tonality in a

side-lit scene (Rule 1). The exposure was 3 seconds at f16 at 100 ISO.

In the photo on the right, I used the Singh-Ray Polarizer combined with

the Singh-Ray

George Lepp 5-Stop solid ND

filter to give me a 121 second exposure at f16. Notice how the grass in

the right-hand photo shows a much greater range of movements, like a

brush stoke painting. As well the clouds streaked across the sky in the

longer exposure and painted more colour and movement into the sky. I

really love the effects of long exposure and combining a polarizer with a

solid ND filter was all I needed to make these images happen.

"In

Photo 11, a polarizer gave me great colours on a grey day (Rule 3) and a

solid ND filter gave me a long exposure to record the windy day in

sweeps of tones.

"Rather than use a UV filter for protection of

the front element of my lens, I use a polarizer instead. For my

photography, a UV filter has very little effect, but a polarizer does. I

simply leave a polarizer on my lens all the time, because for me, this

filter is essential to help me capture the images I see in the world."

To learn more about Darwin's photography and check his other educational resources, stop by

his website or visit

his blog for the latest information.